Herding, Warfare, and a Culture of Honor: Global Evidence

A culture of honor is a bundle of values, beliefs, and norms that induce people to protect their reputation by answering threats and unkind behavior with revenge and violence. According to a well-known hypothesis from social psychology, such a culture of honor reflects an economically-functional cultural adaptation that arose in populations that depended heavily on animal herding (pastoralism). However, to date, the available evidence is restricted to specific contexts (often the U.S. South) and small-scale elements of aggression.

Jan de Visscher (1643), Shepherds from their flocks to a meal landscapes with cows and shepherds

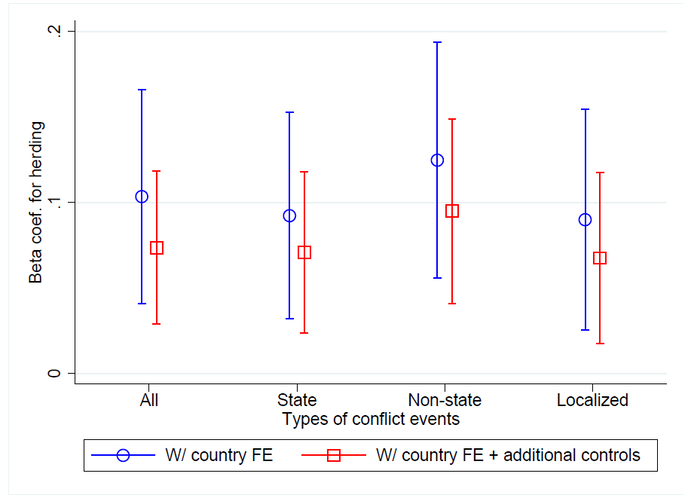

My coauthors and I test this idea at a global scale using a combination of ethnographic records, historical folklore information, global data on contemporary conflict events, and large-scale surveys. The linked data allows us to examine the relationship between importance of herding in pre-industrial societies and contemporary measures of conflict and individuals' propensity for revenge taking. The causal effects are identified by comparing ethnolinguistic groups that reside within the same country but potentially differ in their historical reliance on herding.

We start by showing that pre-industrial ethnic groups that relied more strongly on herding did indeed develop a culture that emphasizes violence, punishment and retaliation, which is revealed by the higher frequency of motifs related to violence, punishment, and retaliation in their traditional folklores. We then show that that populations that historically relied on herding to a greater extent have more conflicts today, with more deaths and longer periods in conflict.

We start by showing that pre-industrial ethnic groups that relied more strongly on herding did indeed develop a culture that emphasizes violence, punishment and retaliation, which is revealed by the higher frequency of motifs related to violence, punishment, and retaliation in their traditional folklores. We then show that that populations that historically relied on herding to a greater extent have more conflicts today, with more deaths and longer periods in conflict.

We then delve into the relationship between herding and a psychology of punishment by leverage a recent globally representative survey dataset that includes rich information on respondents' willingness to take revenge and punish other people for unfair behavior. Looking both within and across countries, we find that the degree of traditional herding is strongly predictive of individual's willingness to take revenge and punish others for unfair behavior.